Contemporary Comics

themes, authors and languages in the italian graphic novel

A production of

Texts: Giovanni Russo

Graphic and pagination: Francesco Bonturi

Translation: Francesca Paglialunga

All images are copyright to their respective owners.

LUCCA CREA S.R.L. – Corso Garibaldi 53 – 55100 Lucca, Italy – P. Iva 01966320465

General privacy information – Cookie policy

8

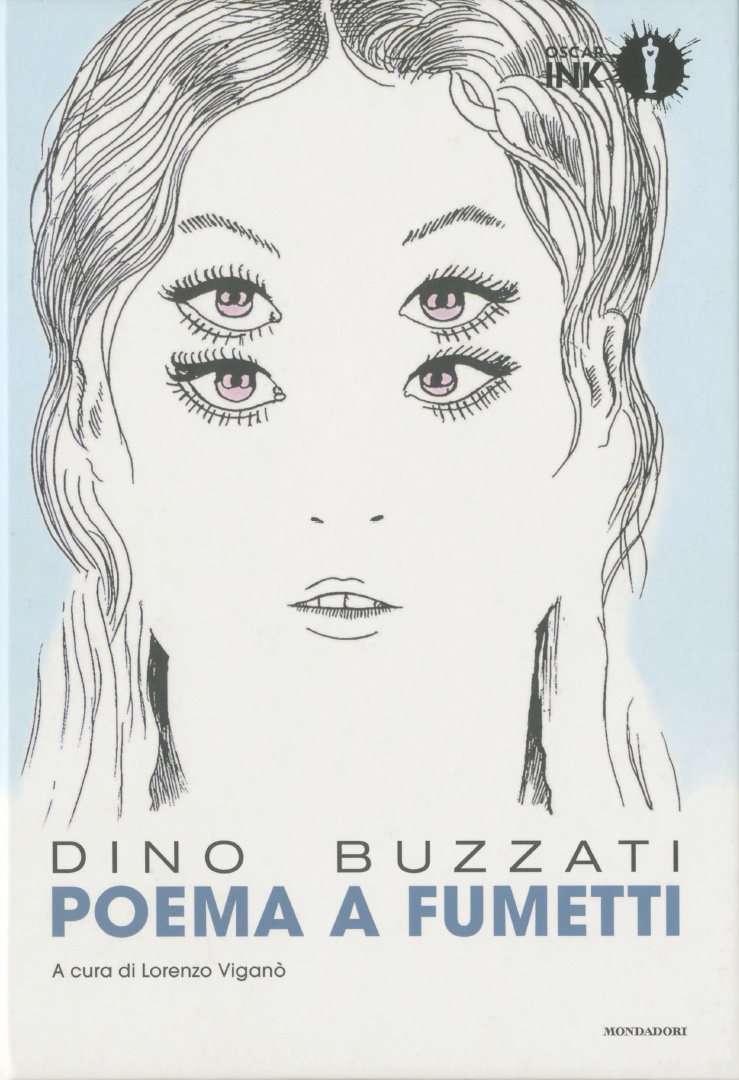

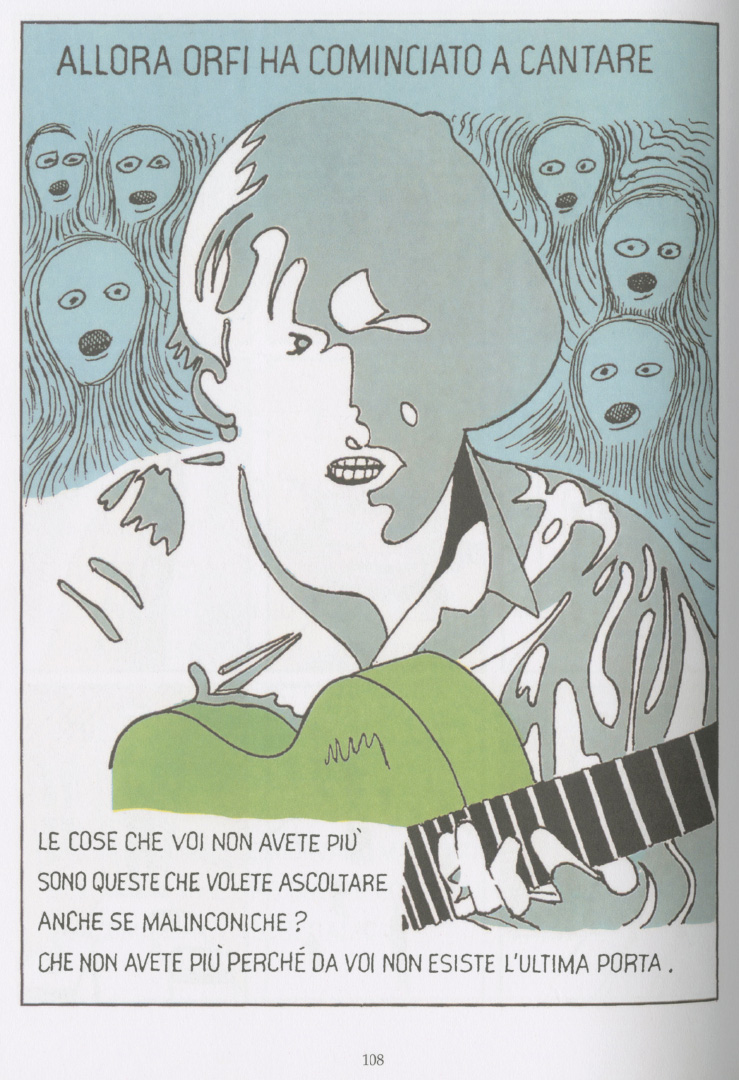

Dino Buzzati, Poem Strip, 1969

Dino Buzzati

Dino Buzzati (1906-1972) is well known as one of the main Italian writers of the 20th century. The Tartar Steppe (1940) – story of an officer who in a desolate fortress awaits the attack of a mysterious enemy that will never arrive – is universally considered his masterpiece. Buzzati however was also a painter, author of paintings often inspired by his beloved comics.

In 1969, combining writing and painting in a very personal form of comics, he produced his Poem Strip, which would nowadays be automatically classified as a graphic novel. The Poem is the most emblematic result of the tremendous curiosity surrounding comics among Italian intellectuals in the 1960s, the season of the great comics authors. The book came out in the same period as Pratt’s Ballad and it is a modern reworking of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. It is the story of the young singer Orfi, who follows his beloved Eura into the underworld, after seeing her disappear through a small door in the wall surrounding a mysterious villa in a fictional street of Milan. In this underworld the dead live on forever, fearless and apathetic, but also desire-less and without real emotions. Using the power of his songs, Orfi makes his way up to his beloved one, but the ending, like it was for his near namesake Orpheus, will be a bitter one.

Compared to literature, painting, or comics, the Poem reveals its eccentric nature of a mysterious object, which nobody from these three fields has been able to find a suitable place for in their own narrative. The truth is that it is only by looking at this work from all sides and simultaneously that the fecundity of one of the most original examples of 20th-century Italian culture clearly emerges.

9

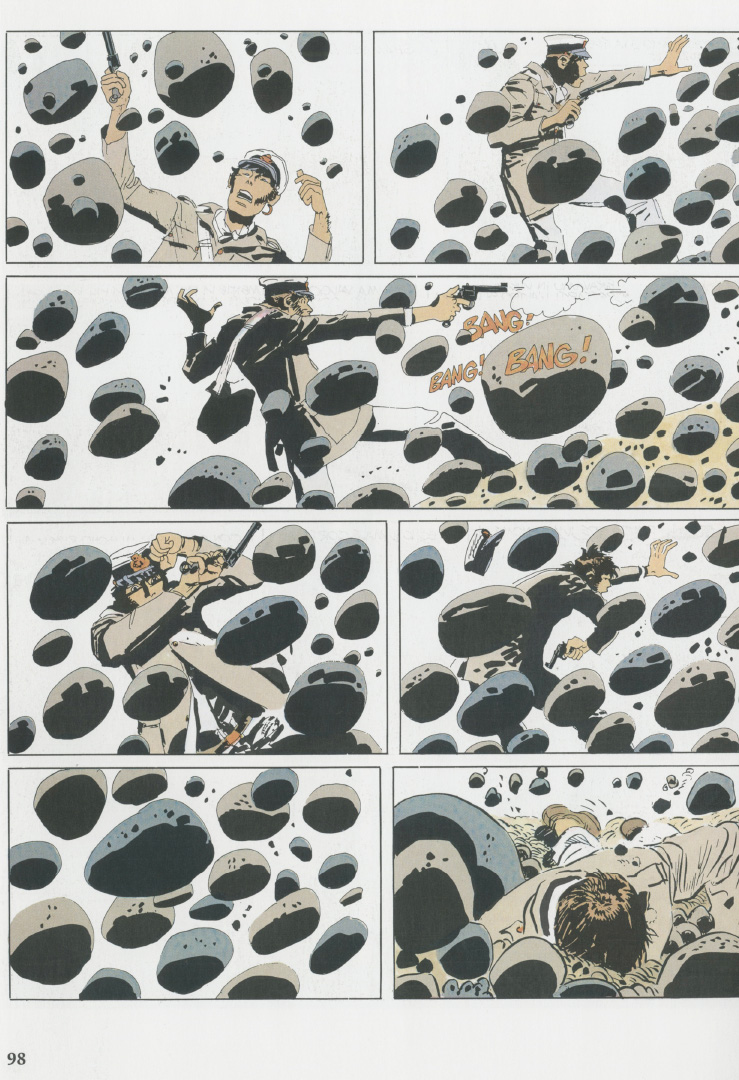

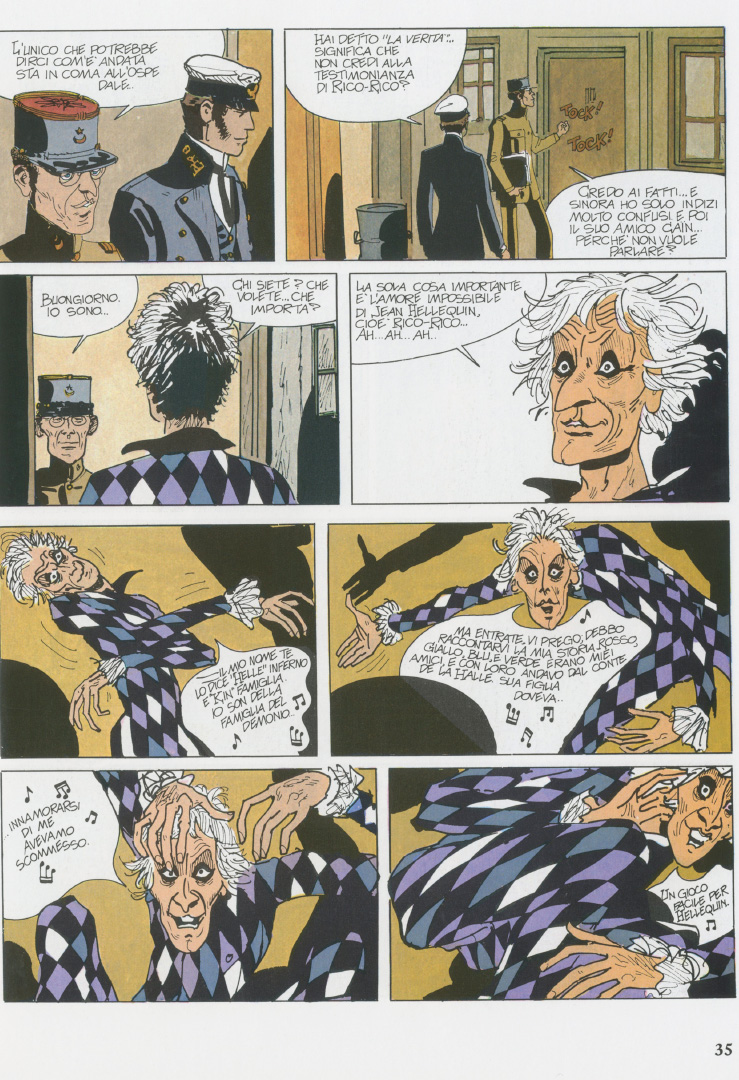

Hugo Pratt, Corto Maltese – …e di altri Romei e di altre Giuliette, 1973

Hugo Pratt

Hugo Pratt (1927-1995) is unanimously recognized as one of the greatest comics authors in the world, and talking about him inevitably means talking about Corto Maltese, his best-known character.

Corto Maltese, sailor and adventurer, first appeared in Ballad of the Salt Sea, a graphic novel published in installments starting in 1967. The most accomplished result of Corto’s adventures and Pratt’s art, however, is the next graphic novel, Corto Maltese in Siberia (original title: Corte Sconta detta Arcana) (1974-1977), which followed a series of beautiful short stories that served to fully develop the character. The Italian title refers to a Venetian court, but the story takes place among Chinese secret societies, in Mongolia, amid the throes of nationalist fervor, and in the pre-revolutionary chaos of Russia, full of warlords who are constantly fighting one another.

Pratt’s greatness lies not so much in his mastery at telling an adventure story as in his ability to turn adventure into a mental condition, into a moral attitude. Pratt does not tell a story to entertain, if not incidentally: he tells the need for adventure, understood as the need to be open towards the world. It is a strongly humanistic position, nevertheless expressed with the characteristic aristocracy of the intellectual, which mirrors the internal aristocracy of the stories, the aristocracy of a “gentleman of fortune” such as Corto. And it is a position that resonates with a veracity that is both timeless and at the same time absolutely contemporary.

10

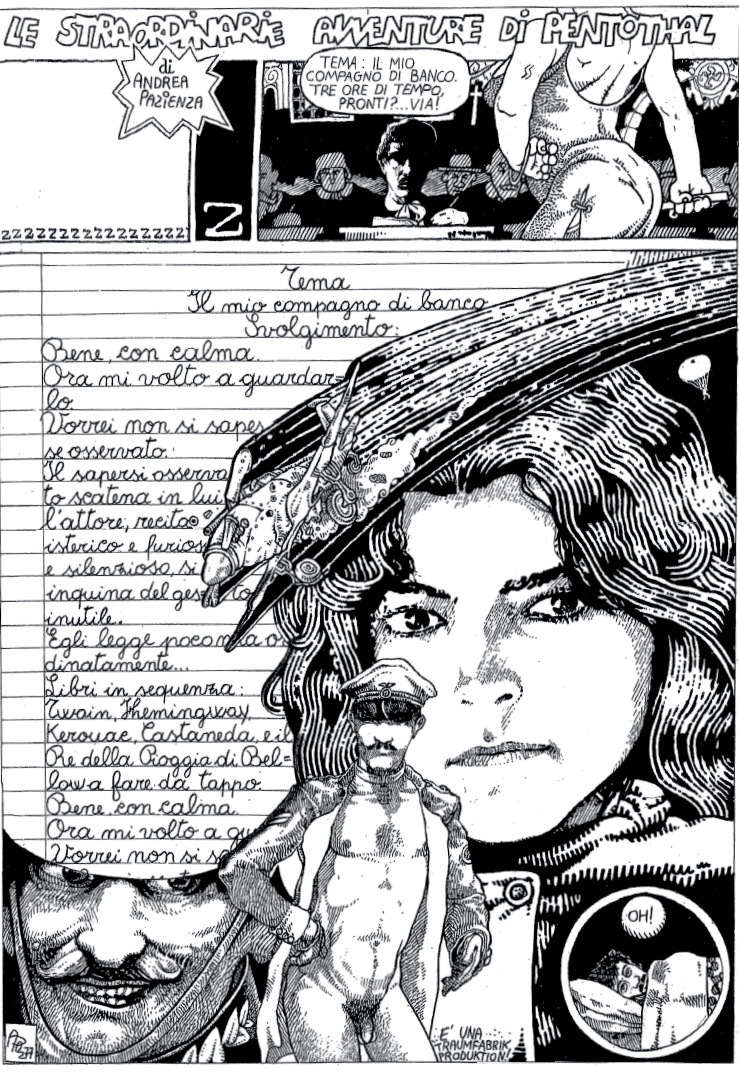

Andrea Pazienza,

Andrea Pazienza

Andrea Pazienza (1956-1988) is a key figure in the history of Italian comics. Despite being one of the most influential Italian comics artists, so exceptional as to be almost unique, he is also one of the most misunderstood.

Pazienza revealed himself immediately as an ace: gifted with an amazing drawing talent, he was able, as he wrote about himself without any false modesty, to “draw anything in any way”, passing abruptly, often within the same page, from hyperrealism to caricatural deformations in both underground and humor/Disney-like style, passing through all possible intermediate variations. His writing was as exceptional as his drawing: his Italian was powerfully communicative, vital and rhythmical, at the same time both elegant and colloquial, full of piercing neologisms, capable of moving effortlessly from a humorous to a tragic style. When one adds his personal charisma to his artistic qualities – his dissolute lifestyle, marked by his drug abuse and early death – one has the legend of the cursed genius, the rockstar of Italian comics.

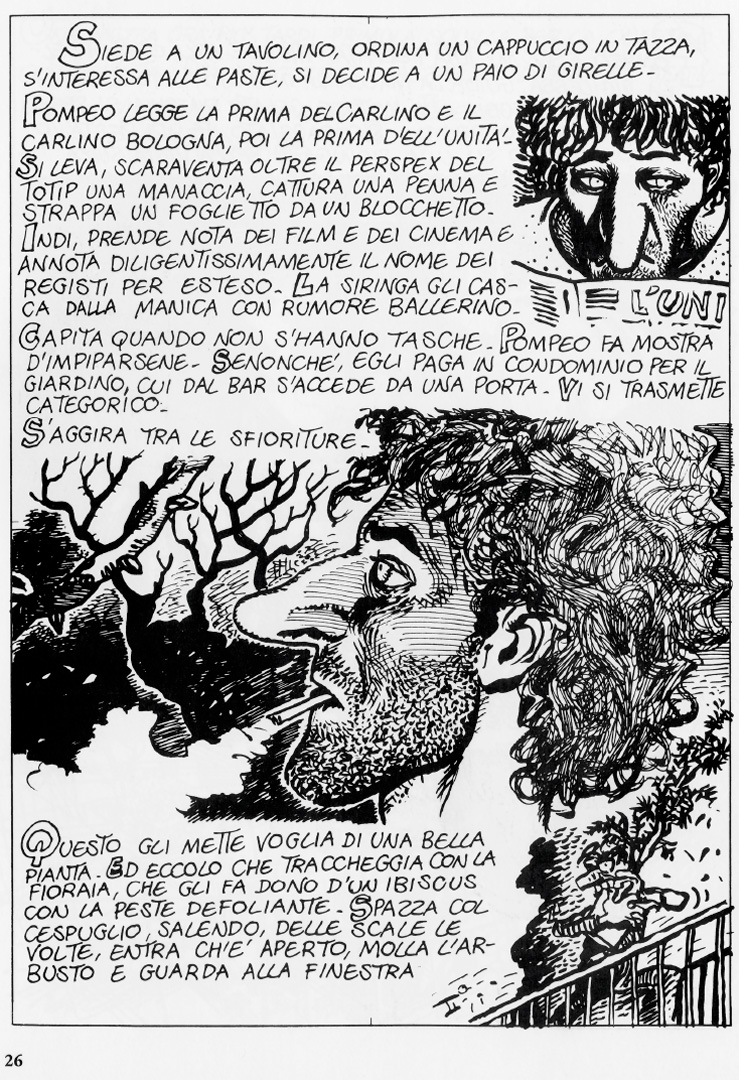

His most important work is the semi-autobiographical graphic novel Pompeo (1985-1987), the cruel and devastating story of the last days of a drug addict’s life and his death by suicide.

Zuzu, Chees, 2019

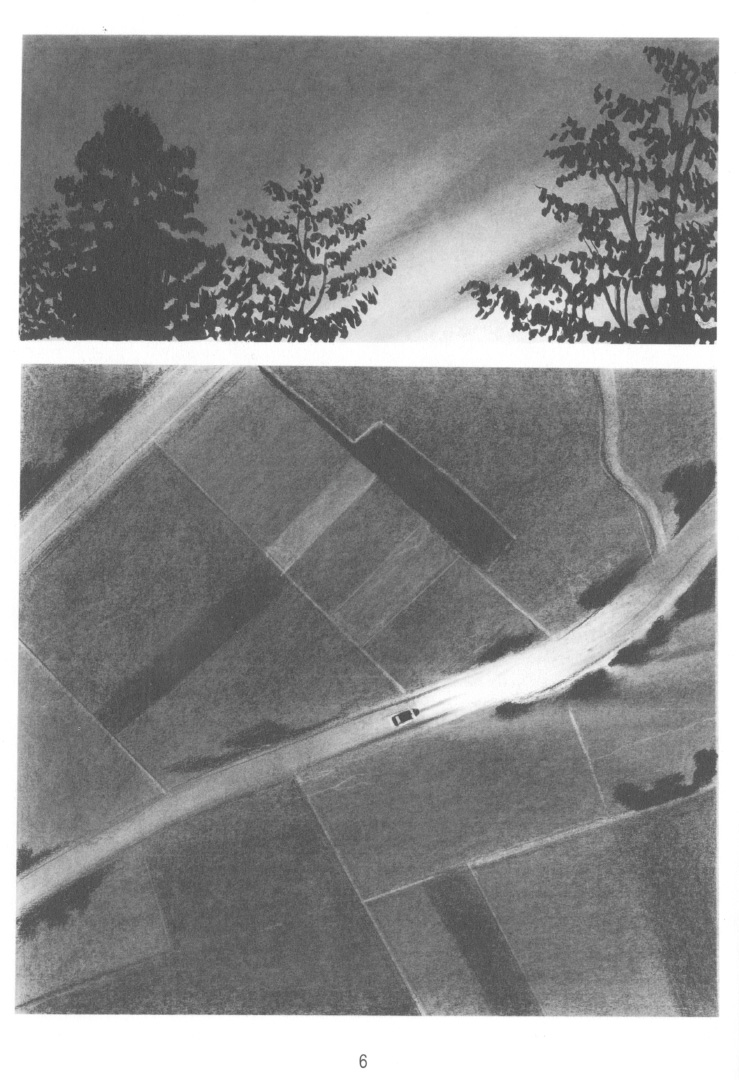

Gipi, La mia vita disegnata male, 2008

12

Gipi,

Gipi

Gian Alfonso Pacinotti, aka Gipi, is the main exponent of the Italian graphic novel in the new millennium. Gifted with amazing sensitivity, Gipi (1963) grew up in a suffocating provincial environment that seemed to offer no hope for the future. After a difficult childhood living on the streets, his considerable drawing talent offered him a way out, both professionally and existentially, initially in fields quite distant from comics, such as graphic design, advertising and illustration. He made a name for himself in comics with Notes for a War Story (2005), with which he won the major European awards. Notes for a war story is a coming-of-age story set in a hypothetical war, also involving places in which the author grew up. It is a semi-autobiographical book, which does not really talk about war. Gipi in fact uses the war as a metaphor that allows him to deal with his difficult childhood, his friends who were destroyed by drugs or ended up on the margins of society living by their wits, and, above all, his sense of guilt because he was able to leave that world, because he survived.

Another one of his best books is Unastoria (2013), which tells of a writer put in a psychiatric hospital after suddenly going crazy. Once again Gipi proposes a semi-autobiographical character struggling with a new sense of guilt, that of the now established author who lives in a world of stories.

In 2016, Land of the Sons is released, in which Gipi returns to a pure fictional story, that is also an acute reflection on fatherhood. In a post-apocalyptic future, a father does everything in his power to bring up his children without having them learn of writing and, as a result, of any memories of the “before”. As much as he does it for their own sake, the children will inevitably end up rebelling.

13

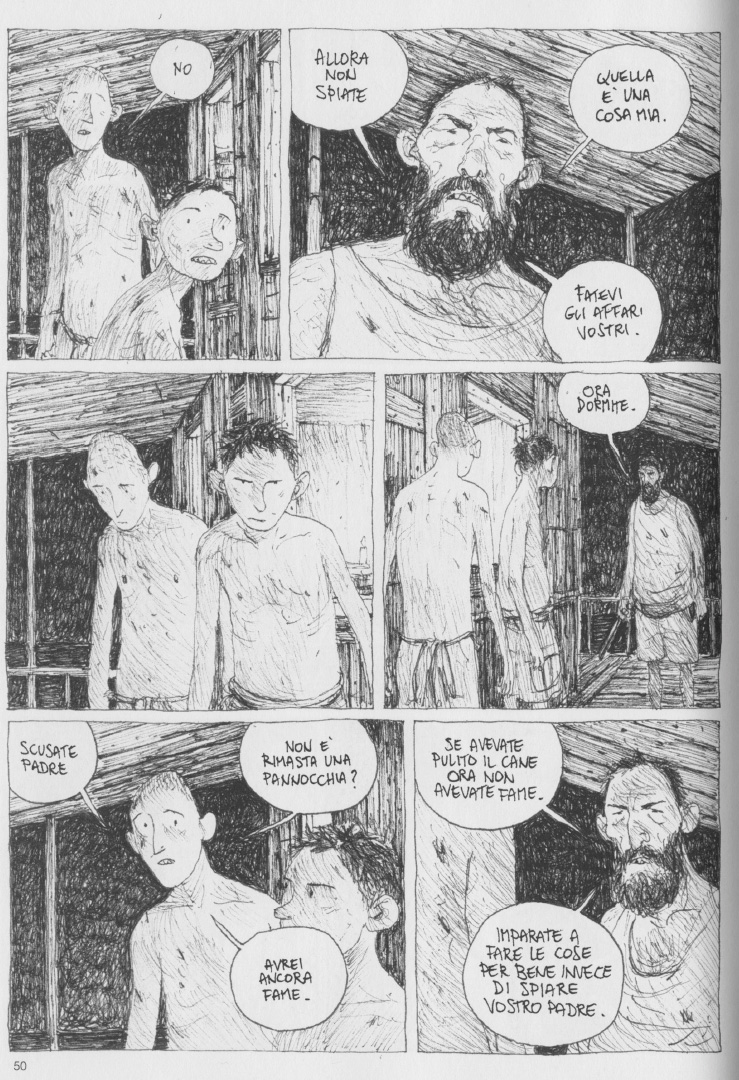

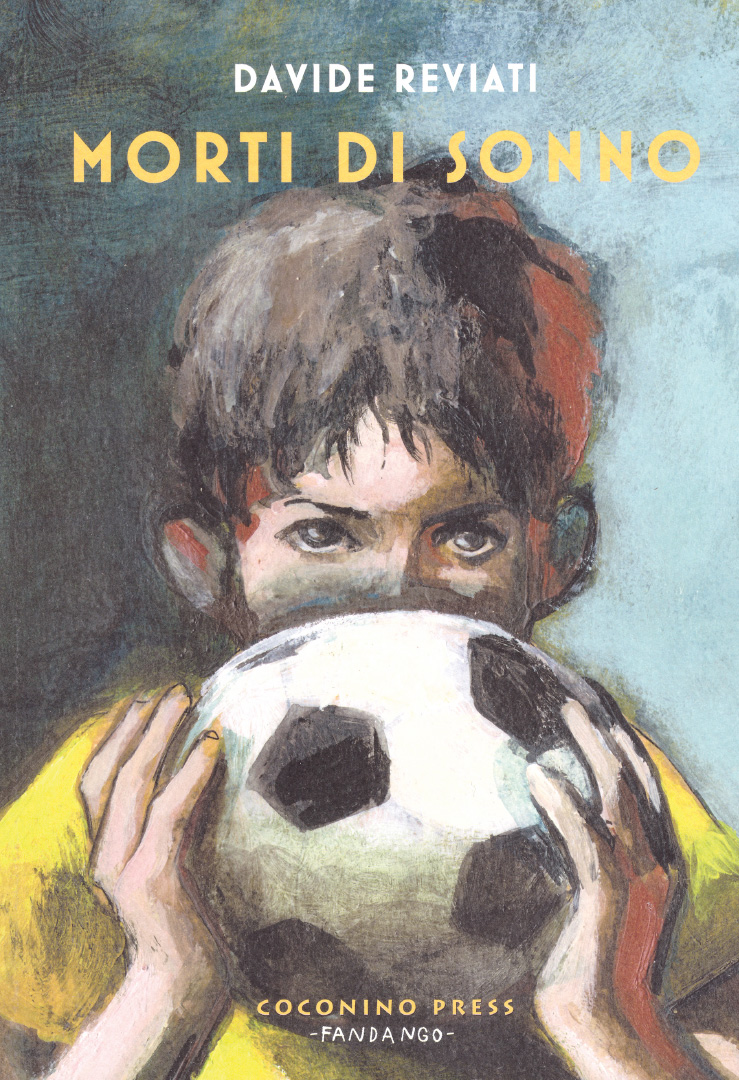

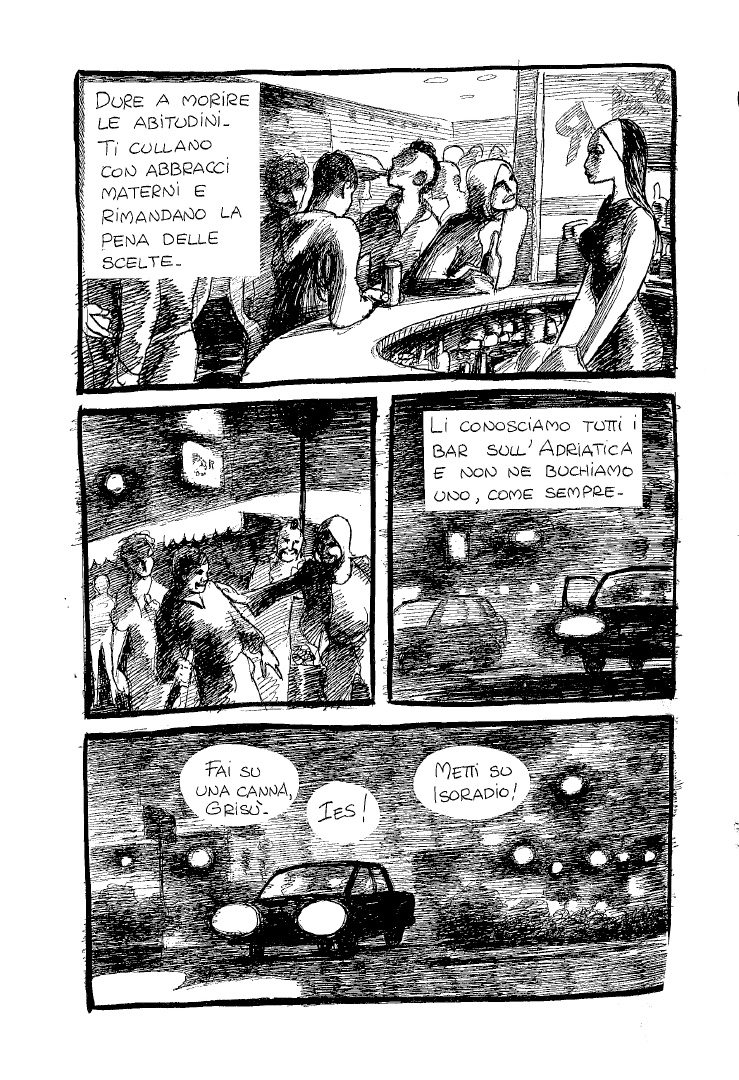

Davide Reviati,

Davide Reviati

Davide Reviati (1966) is one of the most peculiar voices in the Italian graphic novel scene. Based on the author’s own personal experiences, Morti di sonno is the story of a group of children growing up at the end of the 1970s in a little town near a big oil refinery. In the shadow of this refinery, with its emissions, its dangers, its presence, which is at the same time both threatening and reassuring, the boys live a decisive period in their lives, represented above all by football, which in Reviati’s story about childhood is tinged with epic hues. The endless games of football link the different parts of a narrative that otherwise proceeds episode by episode, individually evoked in the dimension of memory. Rather than a linear story, however, these different episodes together form a choral affresco.

While Morti di sonno talks about childhood, Spit Three Times deals with adolescence, using the same semi-autobiographical premise, the same copious, flowing episodic structure (the book is more than 500 pages long) and a similarly choral cast. The protagonists are teenagers living in an anonymous rural province. While in the previous book football was the common thread, this time it is the relationship with a family of gypsies living in the outskirts of town, with whom the protagonists establish an ambiguous relationship. Like everybody else, they are distrustful of and racist towards the family, but there is still nevertheless the chance for basic exchanges which, despite their differences, never carry a prejudicial exclusion.

Silvia Ziche, Lucrezia, 2010

Vanna Vinci, Doppio sogno, 1994

15

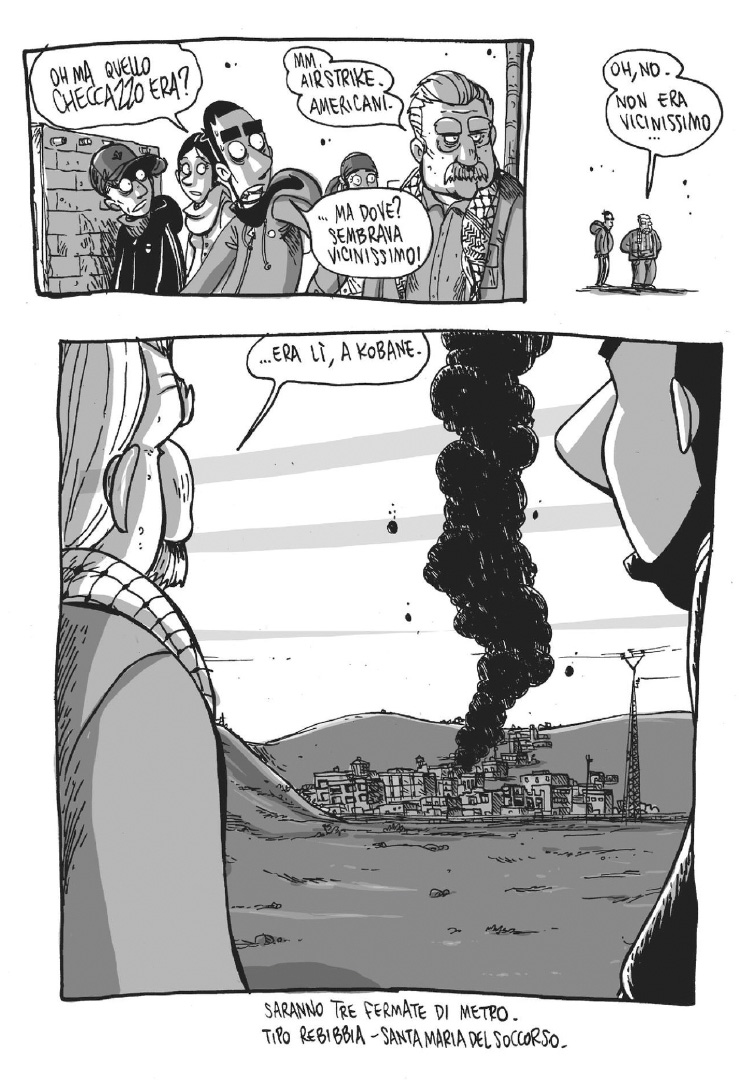

Zerocalcare,

Zerocalcare

Zerocalcare, pseudonym of Michele Rech (1983) is the most relevant Italian editorial case since the beginning of the graphic novel era. He grew up in the working-class neighbourhood of Rebibbia in Rome and began writing about his everyday life experiences in his own personal blog, using short stories full of postmodern humour and pop culture references. In addition to himself, there is an entire cast of supporting characters based on his friends and relatives, and an armadillo – an imaginary character that enables Zerocalcare to depict his internal dialogues. What emerges from his stories is a generation living in a precarious situation, trapped between odd jobs and deadlines, with a lifestyle that is necessarily post-adolescent, in which the only unifying values appear to be neighbourhood pride and mass culture references. His representation of a generational identity has made his posts spread so rapidly that he was soon obliged to switch to a longer format on paper, with results saved by a huge success.

Kobane Calling (2016) is Zerocalcare’s most mature and accomplished book. Zero, together with some friends and activists, goes on two journeys to Kobani, in Syrian Kurdistan – the city that has become the symbol of the Kurdish population’s resistance to ISIS during Syria’s long civil war. Zerocalcare the character, with whom readers are by now familiar, this time assumes a different role: he acts as a guide and questioning conscience dealing with an massive issue, which is not just the specific problem of the Kurdish war, but the more general topic of the dramatic, often hypocritical dialogue between the West and the Islamic world.

16

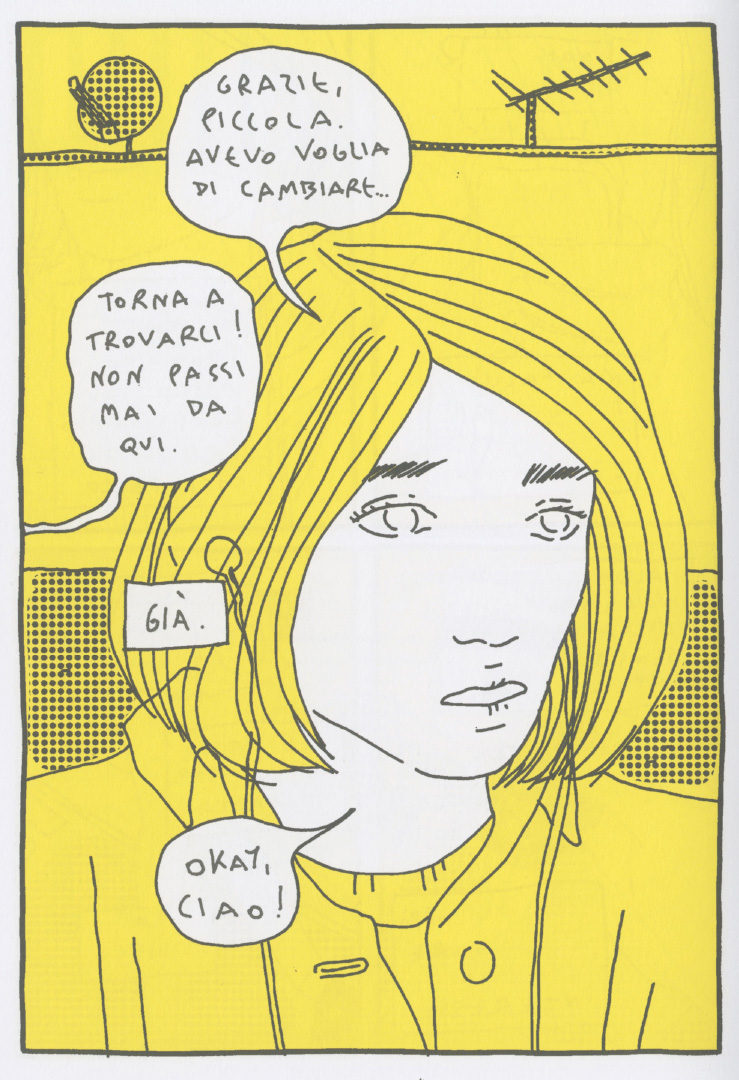

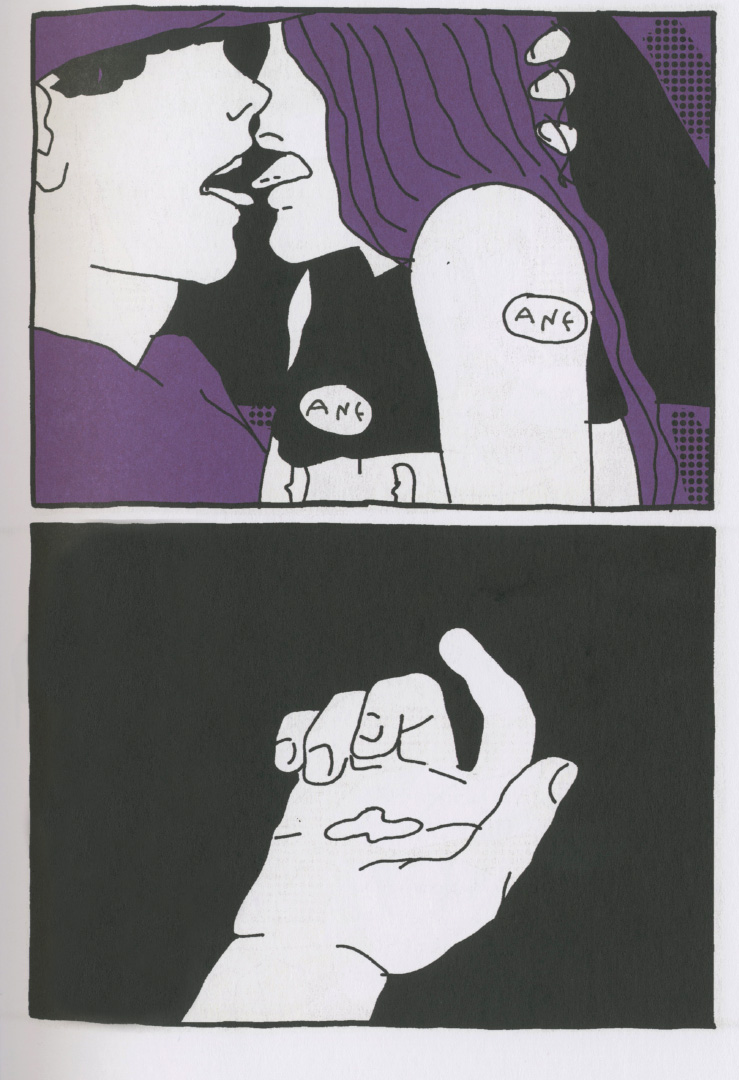

Fumettibrutti,

Fumettibrutti

Josephine Yole Signorelli (1991), aka Fumettibrutti, has made a name for herself publishing her comics strips on social media. They are provocative pills, tackling straightforwardly and without any sense of guilt themes such as sex, feelings, identity, diversity, loneliness. Her style is deliberately unadorn, capable of visually conveying the existential emptiness from which her characters, and with them the author, desperately want to get out. Her first book, Romanzo esplicito (2018) is the semi-autobiographical story of a love ended badly. With her next one, P. La mia adolescenza trans (2019), Signorelli totally exposes herself to describe the difficulties, the determination, the pain and the pride of her path of self-acceptance as a young transsexual living in a hostile and conservative society.

Ausonia, Interni, 2008-2011

Giacomo Nanni, Cronachette, 2007

18

Igort,

Igort

In his constant search for a geographical and chronological “elsewhere”, with an attitude that results in languishing yet cerebral exoticism, Igor Tuveri, aka Igort, transposes his various interests into introverted and refined comics, rich in both textual and visual references. Italian comics should give Igort credit for having founded Coconino Press, the first publishing house to introduce comic books into bookshops in a congruous manner, paving the way for the arrival of the contemporary Italian graphic novel.

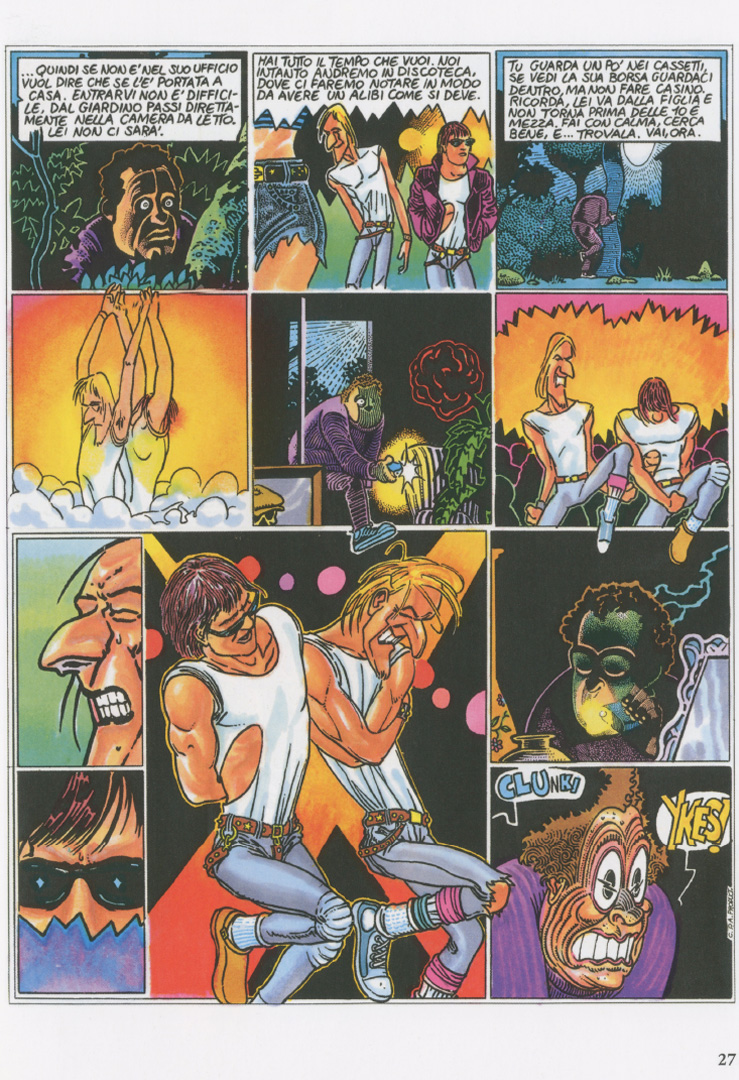

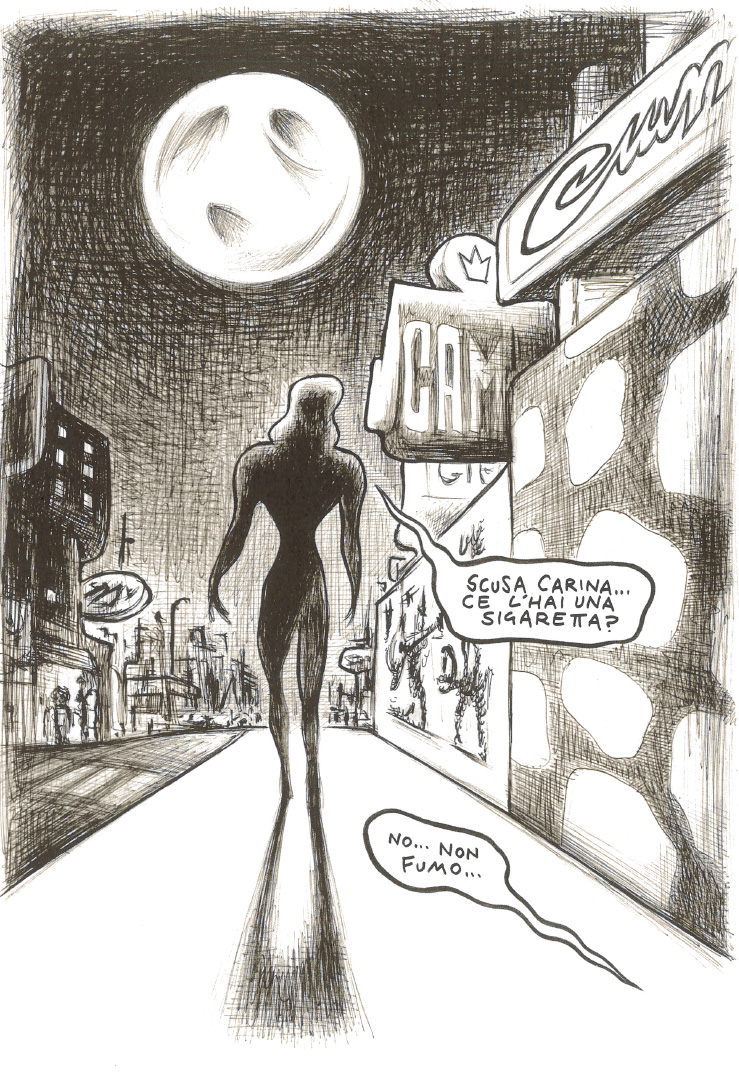

5 is the perfect number (2002) is his best-known work, that has recently also become a movie highly regarded by critics, marking the author’s debut as film director. It is a noir story set in Naples, in which an old, retired Mafia hitman comes out of retirement to avenge the death of his son, also a Mafia hitman, who was killed by his intended victim after being betrayed. Combining European (French noir movies in Melville-style), American (Chester Gould and his stylisations, without however reaching his gruesome extremes) and Oriental (the hard-boiled Hong Kong movies) influences, it is a noir story that is both traditional and original, above all as regards its Neapolitan setting. It is in fact not merely a geographical detail: as in an anthropological study of the Mafia, Igort efficiently describes familialism, the hypocritical closeness to religion, and the pride in belonging and “getting a job done properly”, even if that job is to kill someone.

19

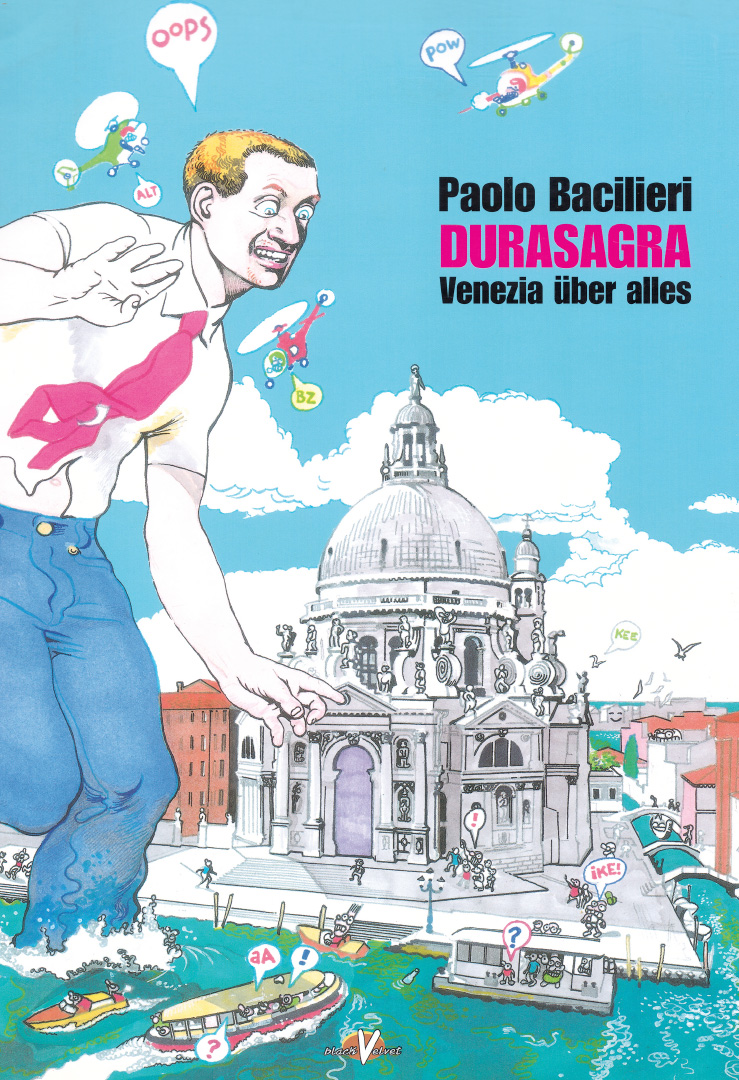

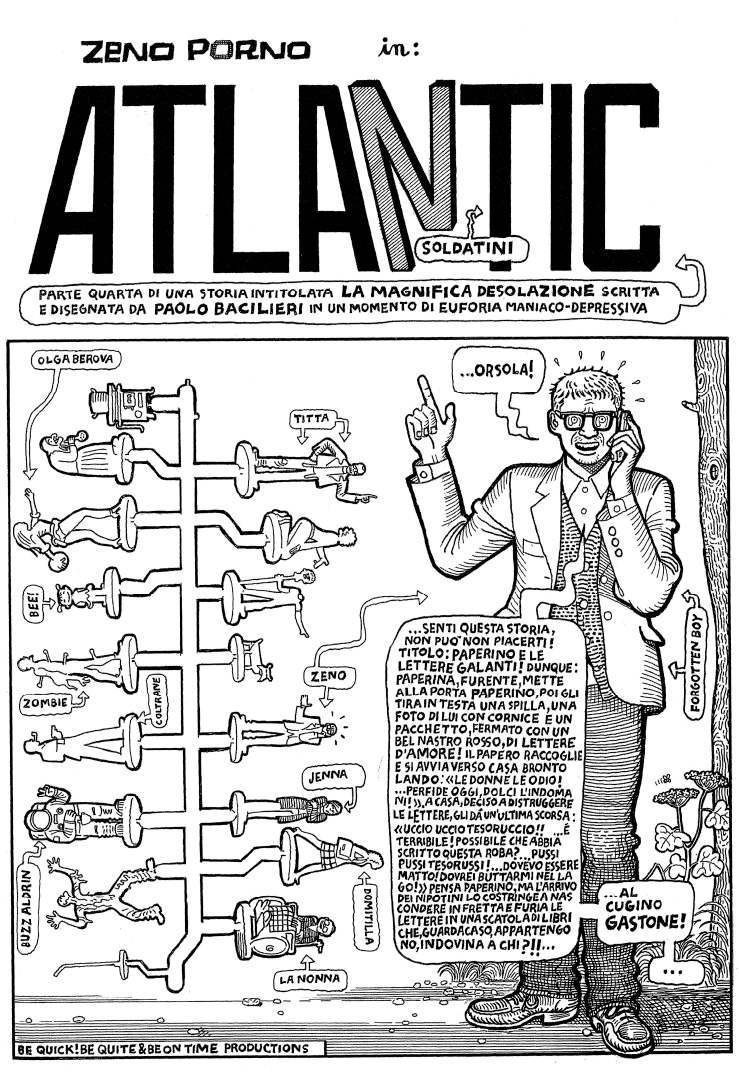

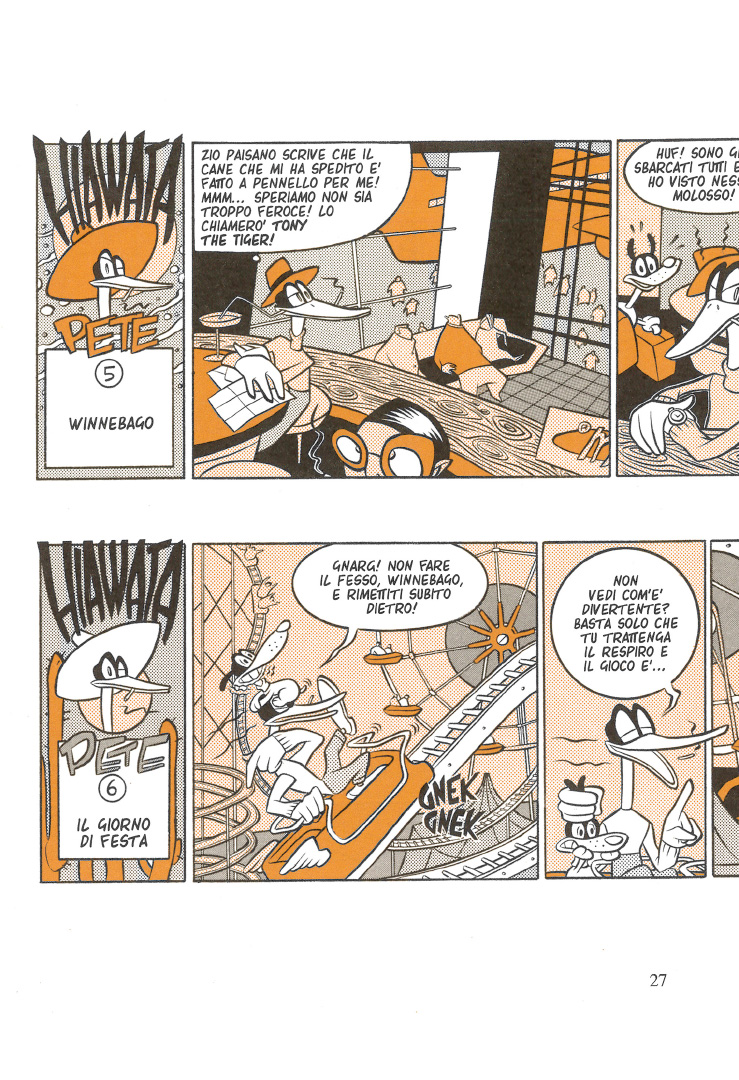

Paolo Bacilieri,

Paolo Bacilieri

Paolo Bacilieri (1965) is an original storyteller of the everyday grotesque. La magnifica desolazione is one of his most successful books, in which he manages to find just the right balance between surrealism and a distorted, but familiar everyday life. In the world of La magnifica desolazione, Zeno Porno, the author’s alter ego, is a Disney comics writer who is struggling to come up with original stories and continuously recycles Carl Barks’ ideas. Moreover, he is in the middle of a love crisis, has a father who is being hunted by a beautiful CIA agent because he is 30 metres tall, and has a friend with a disfigured face who involves him in an unlikely expedition to the moon, with everything taking place in an Italy invaded by zombies who turn out to be harmless precisely because they are Italian. The grotesque setting serves merely to emphasize the disorientation felt by a man in the midst of a personal and professional crisis. In the end, it is a banal vision, that of a family of foreign tourists on a boat trip to the Venetian island of Torcello, that triggers in Zeno his decisive epiphany: the awareness that at a certain point, for unfathomable reasons, unhappiness dissipates and hope comes creeping back.

Zeno Porno returns in Fun (2016), in a head-spinning puzzle that, using the history of the crosswords as a narrative gimmick, equates human existence to an interlocking game, which seems impossible to solve, but which in the end, in one way or another, provides all the necessary clues.

20

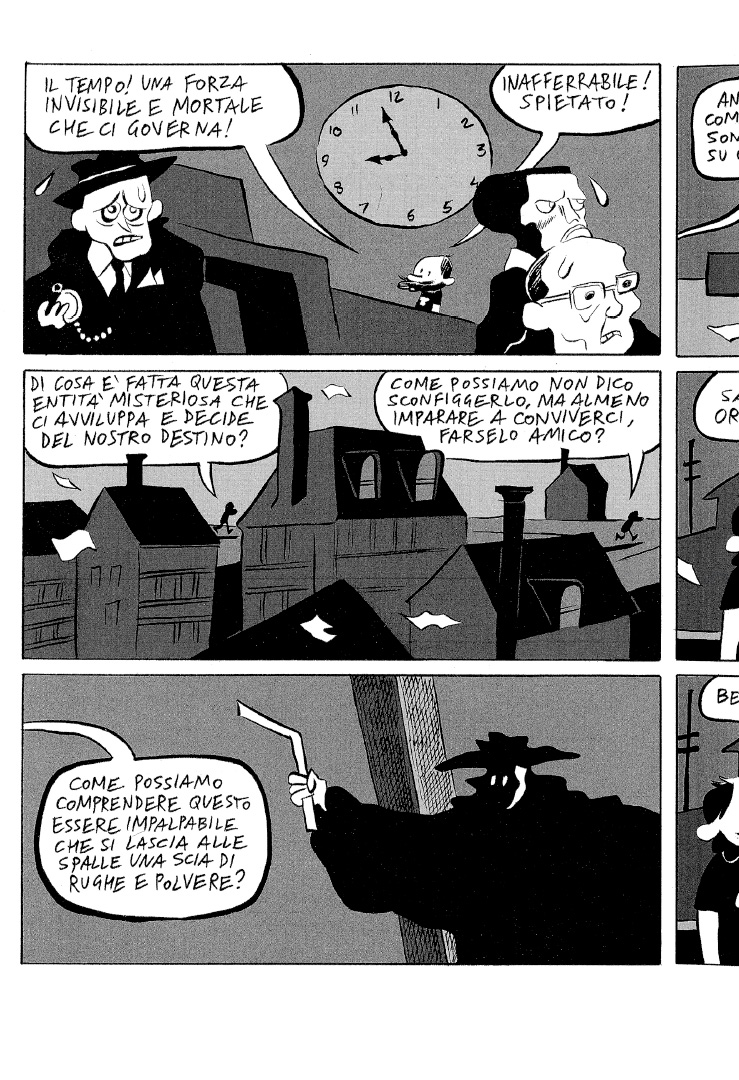

Tuono Pettinato,

Tuono Pettinato

Easy-going but also well-read, follower of his own personal way to “philosophical speculation with little drawings”, Tuono Pettinato (pseudonym of Andrea Paggiaro, 1976) is one of the most peculiar voices in the contemporary Italian comics scene. His nom de plume comes from Borges, and is in itself a statement of his poetics. Starting with a humorous, and in its lightness almost childlike, stylisation, mixing seamlessly references to high culture with others that are brazenly pop, Tuono Pettinato expresses an amazing irony in what might seem simple, albeit useful works of cultural dissemination, but are in fact original approaches to understanding drawn on paper. Often a character in his own comic books, he draws caricatures of himself as a kindhearted heavy metal fan: a short, bald man with a beard and a stylised skull on his T-shirt.

Among his main books Garibaldi. Resoconto veritiero delle sue valorose imprese, ad uso delle giovani menti (2010): it is the true story of Garibaldi, told in a way that is ironical, but not trivial, as regards both the actions and opinions of the Hero of the Two Worlds. The book does not hide Garibaldi’s rather naive idealism, his visceral hatred of the Pope and priests, or his hostility towards Cavour and politicians. Tuono also takes this opportunity to satirise the Italian educational system, which turned Garibaldi into a sort of saint

Corpicino (2013) is a very hard-hitting pamphlet, written as a dark fairytale, on how the media turn suffering into entertainment. When a child is killed, the media circus goes into a frenzy and the child’s murder is merely the first, tragic event in a series of despicable actions.

Davide Toffolo, Très!, 2007

Lorenzo Palloni, La lupa, 2019

22

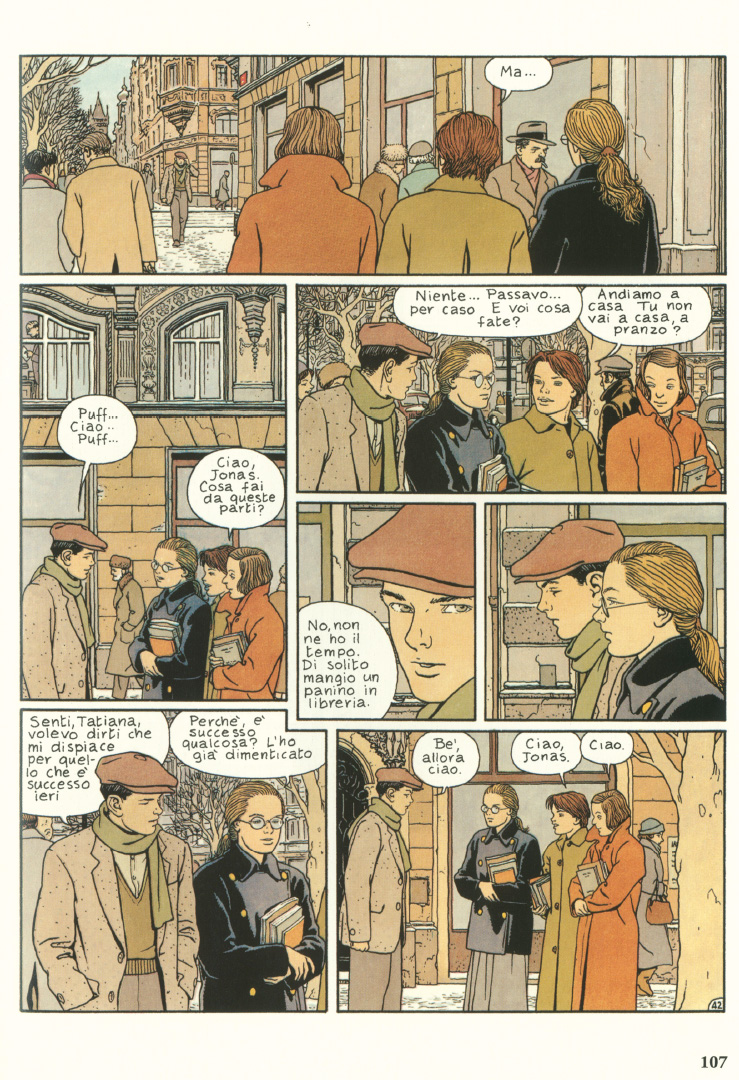

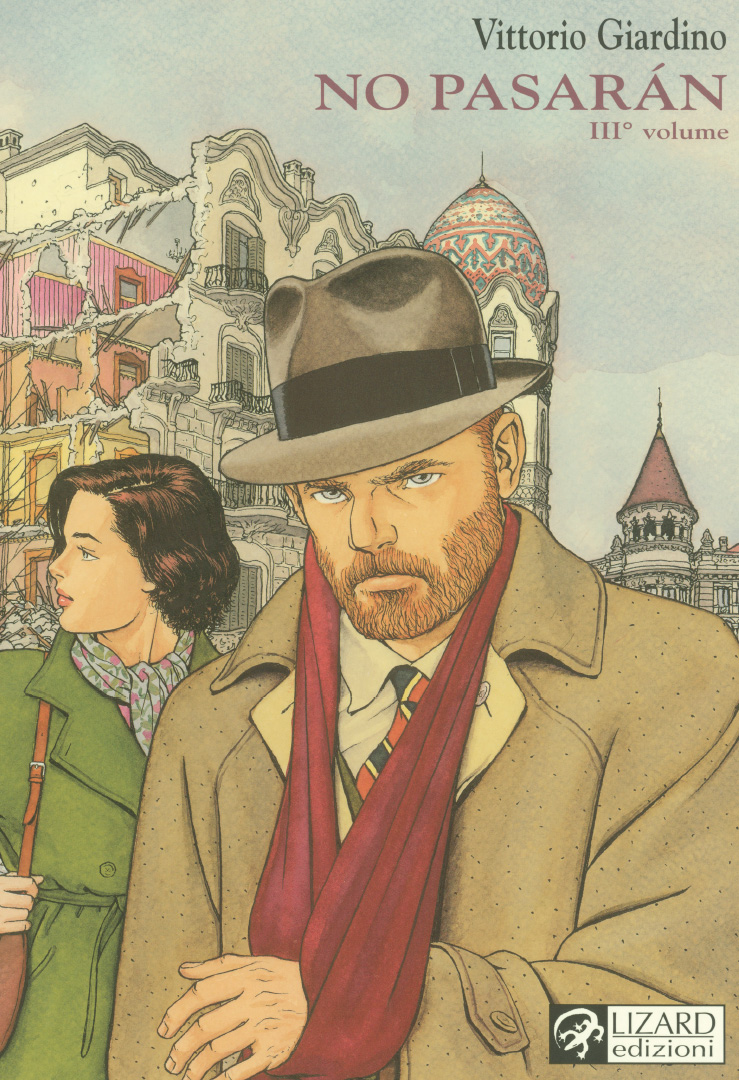

Vittorio Giardino,

Vittorio Giardino

Vittorio Giardino (Bologna, 1946) is above all an excellent storyteller, who builds his plots meticulously, creating solid frameworks where you want to identify his training as an engineer. For his drawing style, Giardino gradually chooses the ligne claire (i.e. clear line) style, that was clearly French influenced, and of which he became the main exponent in Italy.

Giardino’s first interest is for History: the typical “genre” characters and narrative devices are at the service of an historical sensitivity that is not centered around major historical events or the main protagonists of history, nor on the “oppressed”, understood ideologically as the class that suffers History. Giardino is, instead, interested in ordinary people, the social fabric, the mentality, the atmosphere, and the political and psychological mechanisms that created the historical context. As a result of a painstaking documentation, the historical interest is particularly evident in No pasaran, in which Friedman’s journeys seem almost merely a pretext to talk about Spain during the Civil War.

The same applies for A Jew in Communist Prague (original title: Jonas Fink), Giardino’s most ambitious work, which, through its protagonist, describes life in communist Czechoslovakia between 1950 and 1968, with an epilogue set in 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Released in three parts over more than twenty years (Loss of Innocence, 1991, Adolescence, 1998, Rebellion, 2017), this complex graphic novel tells the story of a boy of Jewish origin who grew up in communist Prague, with his father in prison for unknown political reasons.

23

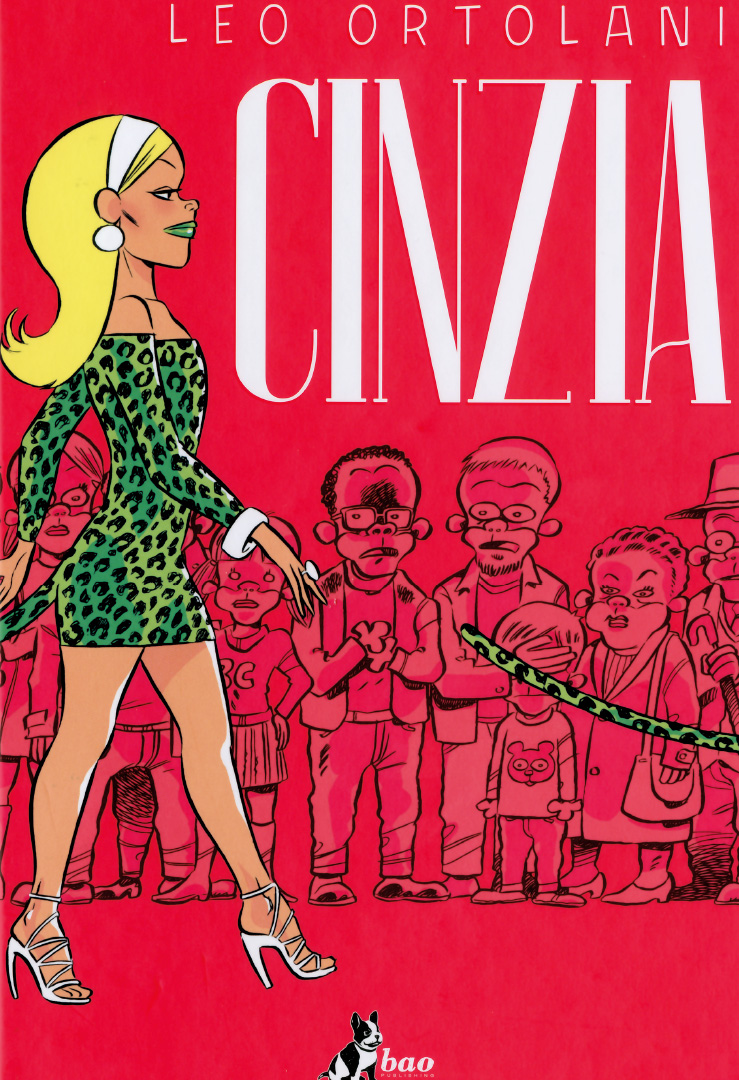

Leo Ortolani, Cinzia, 2018

Leo Ortolani

A superhero enthusiast and a never-ending source of innate humor, Leo Ortolani has turned a self-published parody of Batman into the phenomenon of the most significant popular comic book of the last twenty years. After the long serialization of Rat-Man, his own character, Ortolani has increasingly devoted himself to the longer format of the graphic novel, using his peculiar style and humor to deal also with sensitive themes. Worth of note is Cinzia (2018), a graphic novel dedicated to a supporting character of the Rat-Man series, a sensitive and careful story about the experience of trans people. His last book, Andrà tutto bene, is a daily chronicle of the Covid-19 lockdown, with which, through social media, he has kept company to many Italians in that difficult period.

24

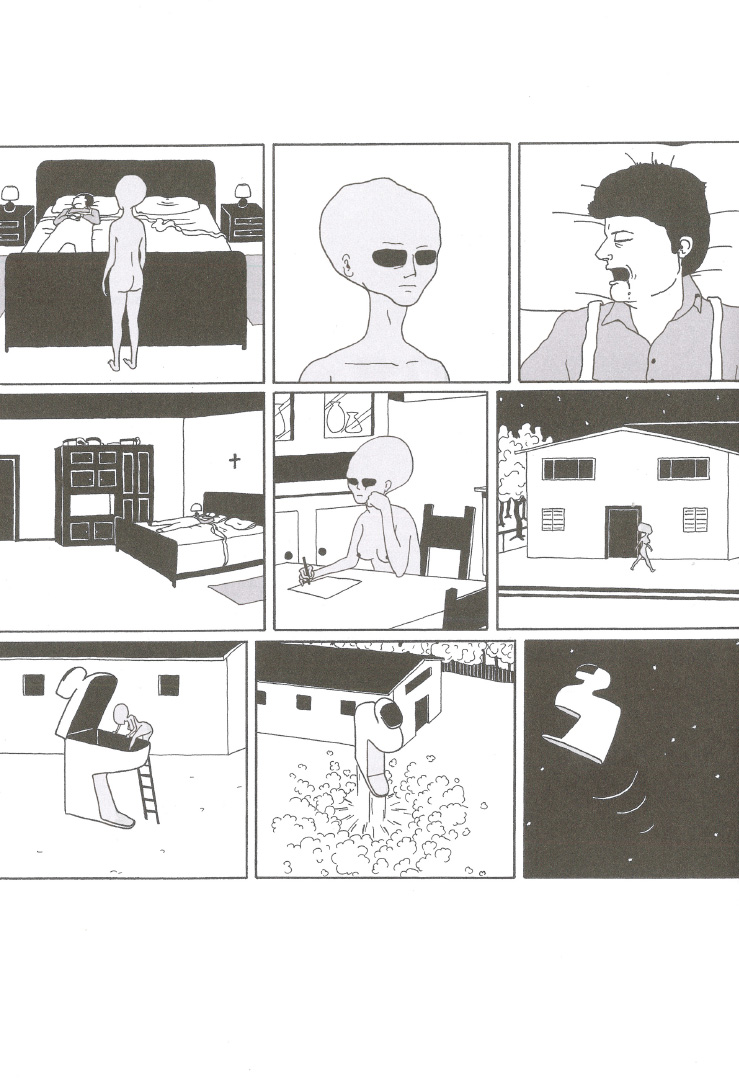

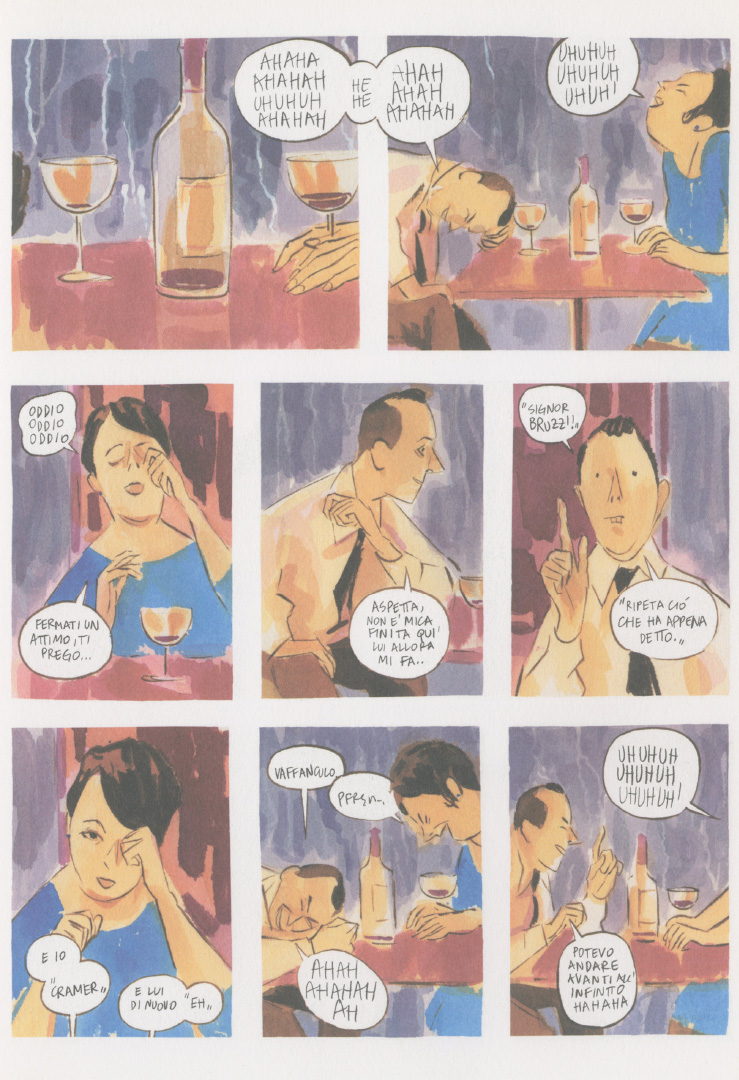

Giacomo Monti,

Giacomo Monti

Author of short stories, Giacomo Monti (1975) made himself known with the anthology Nessuno mi farà del male, which turned out to be one of the best Italian comic books of the 2000s. Monti’s stories are essential, minimal, and at a first glance realistic, but they sometimes present a fantastic twist that mainly serve to highlight the little absurdities of everyday life.

His best stories are authentic little gems. Camicia tells the story of the encounter between a man and a prostitute, but focuses on their idle chatter after sex, when she criticises him for the way he wears his shirt. Trans is a pitiless story of just two pages, in which two men approach and violently attack a transsexual. Several pages later, Trans 2 overturns the original situation, showing the vendetta of the transsexual, who has now turned into a monster and kills his aggressors. Nessuno ti farà del male –the title is the same as the anthology one, apart from a different pronoun– is the story of a surreal “marriage” crisis of a female alien who landed in the field of a farmer, who, as time goes by, starts to treat her as his wife.

Monti’s protagonists are prostitutes and their clients, waiters and waitresses, bar staff and con artists – a small slice of humanity, captured in tiny, enlightening moments. Even though the minimalism he uses leads one to think that his approach is realist, the opposite is, in fact, true. It is in this banality that Monti depicts epiphanic, conclusive moments.

Leila Marzocchi, Niger, 2005-2017

Lorenzo Palloni and Martoz, Instantly Elsewhere, 2018

26

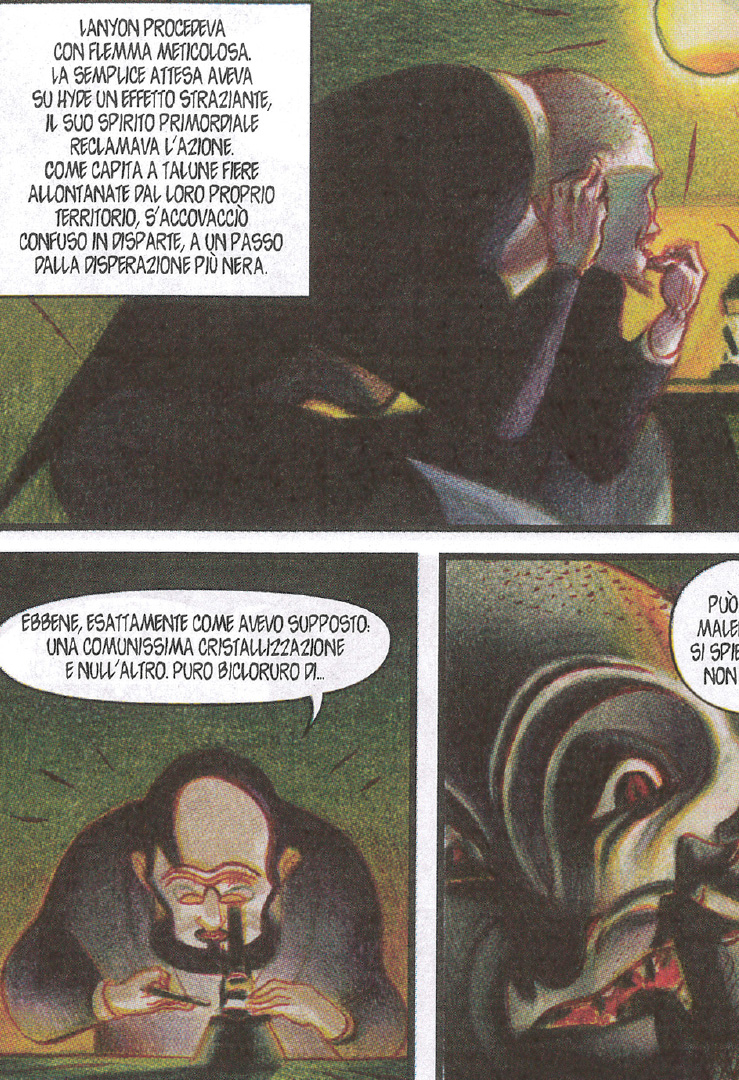

Lorenzo Mattotti

Lorenzo Mattotti

Lorenzo Mattotti (1954) is the author of refined, introspective comics that are not focused on storytelling or figuration, but on depicting what cannot be depicted: the changing emotions that animate an inner landscape in constant flux. Distant from both the realism of popular comics and any other codified style, Mattotti adapts to his inner search a fluid, ever-changing style, capable of switching from an intense chromatism to a graphic black and white, from expressionistic blotches of colour to a soft, sinuous line that is always elegant.

Even though he is quite happy to write the texts, for his comics production Mattotti usually prefers to collaborate with several scriptwriters, the most assiduous of whom is his companion Jerry Kramsky – pseudonym of Fabrizio Ostani (1953) – an old friend of his. It is with Kramsky that he made Fuochi (Fires, 1984), which marked a watershed in Mattotti’s career, making him truly famous both in Italy and internationally. It is a variation on the Conradian atmospheres of Heart of Darkness, in which nature becomes a deforming mirror of the characters’ inner obsessions.

Still in collaboration with Kramsky is Mattotti’s latest book, Guirlanda (2017), the most imposing he has ever made: almost four hundred pages for ten years of work. It is a story somewhere between myth and fable, a fantasy tale vaguely inspired by finnish Moomin, in which the magical world evoked by Kramsky’s text seems designed to enhance Mattotti’s refined illustrative skills.

27

Francesca Ghermandi,

Francesca Ghermandi

Comics by Francesca Ghermandi (1964) are neither realistic, nor narrative in a traditional way, and, at the same time, they have no explicitly countercultural or underground aspirations. Her comics are characterised by a marked degree of synthesis in what is a melting pot of the most disparate contemporary artistic experiences: painting, design, narrative, and even music. Experimental, synesthetic, potentially difficult comics. Ghermandi, who is also an illustrator, applies her remarkable visual talents to this basic approach, creating her own personal pop universe with its very distinctive dark elements.

Her first graphic novel is Grenuord (2005), which tells the story of a grotesque skull-faced character attempting to escape an oppressive relationship and create a new life for himself. In the end, the only solution is for him to flee yet again, fully aware that nothing has really changed.

With Cronache dalla palude (2010) she reaches full maturity as an author. The book, which is no longer centred around a single protagonist, weaves a choral story set in a grotesque world, suspended between doleful tones and glimmers of hope.

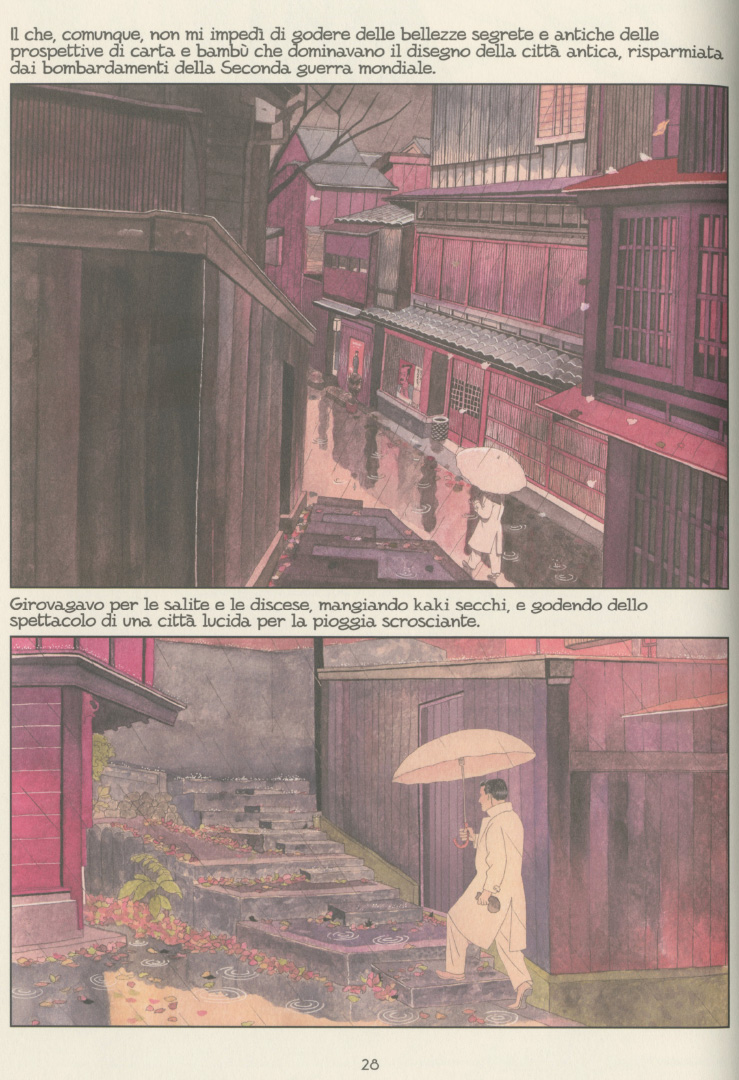

28

Gabriella Giandelli,

Gabriella Giandelli

Gabriella Giandelli (1963) is an elegant, sophisticated author, who pays great attention to the interior dimension of her characters and who is also capable of evoking intimate, suspended atmospheres.

Interiorae tells the story of the Great Dark, who lives in the basement of every apartment block and who feeds on the dreams of the tenants; serving him, a white rabbit, invisible to everyone. One day, however, a young boy sees the rabbit, which is the omen of an impending disaster. The urban landscape and the shared life of the tenants, examples of human diversity, are depicted with great participation and it is difficult not to imagine the author observing her characters with the same curiosity and affection as the rabbit does.

The protagonist of Sotto le foglie, probably her masterpiece, is a mysterious supernatural observer portrayed as a bald man, with dotted lines on his head and around the eyes. The nameless observer arrives in a village in the forest, attracted by a voice full of anger and sorrow. A bit at a time, the drama emerges of a child who died years earlier in the forest, and the story of his now middle-aged brother and his elderly mother, who played a part in the boy’s tragic accident. Giandelli’s quiet and suspended atmospheres perfectly represent the magic of the forest, which in turn is perfectly suited to the air of mystery surrounding the protagonist and to the secret the human characters conceal at the bottom of their hearts, as if buried beneath the autumn leaves.

29

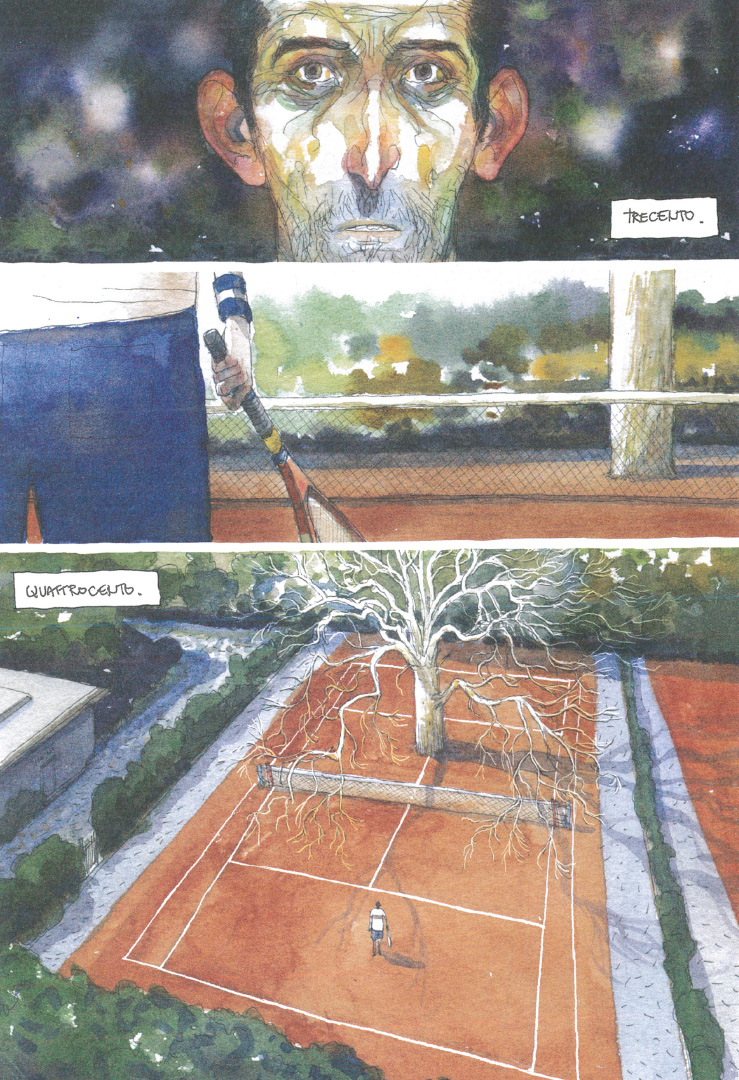

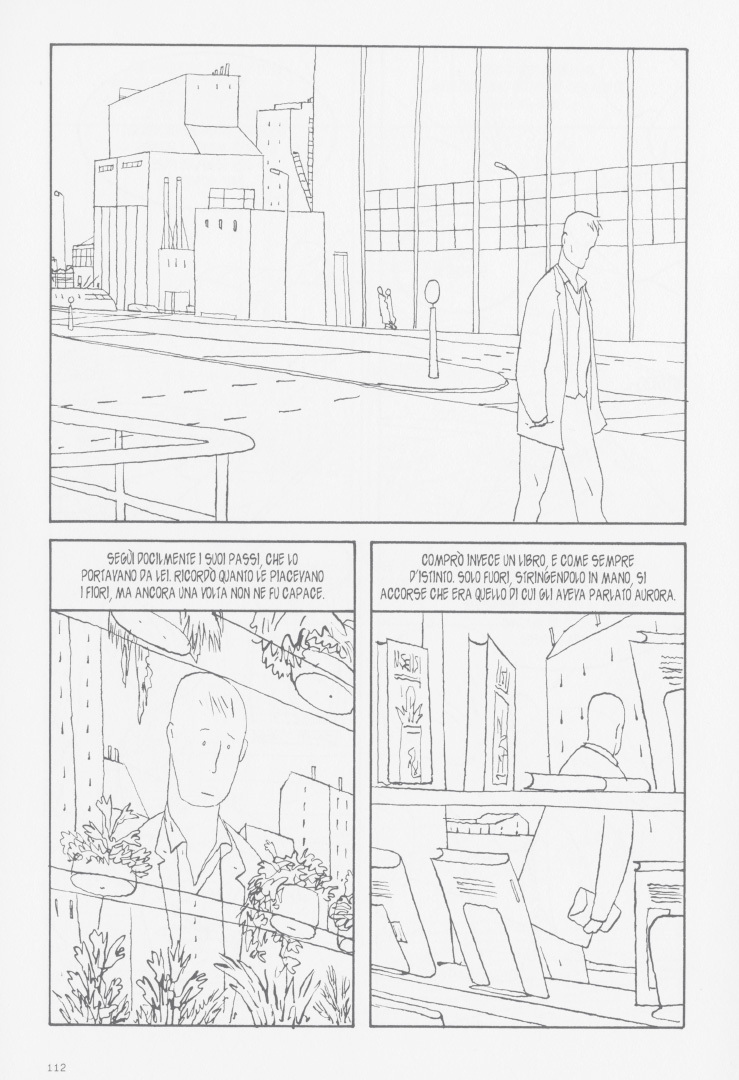

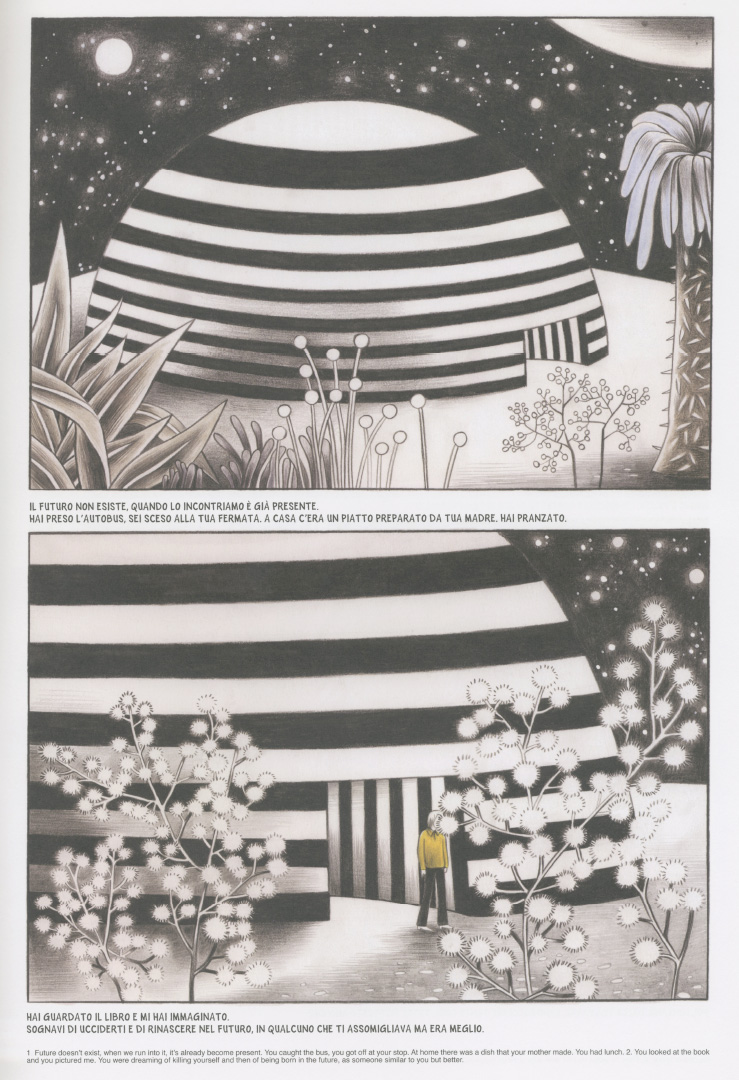

Manuele Fior,

Manuele Fior

After revealing his talent at a young age, Manuele Fior (1975), an architect by training, is now one of the most highly appreciated Italian authors of graphic novels on an international level.

5,000 Km Per Second (2010) is his first big success, and it’s the story of a decades-long love triangle. He and she love each other, they break up, they get lost in the whirlpool of life that takes them apart. Eventually they meet again, years later, in the small provincial town in which they first met, but there is only room for memories and regrets for them now.

Fior proves to be a sophisticated author, cultured, delightful to read and to watch, fascinated by physical and psychological details, and also by the hidden motivations of the behaviors he depicts with unmatched spontaneity.

In The Interview (2013) Fior confirms all his strengths: the extremely natural dialogues, the fluidity of the direction and storytelling, and his interest in elusive relationships that leave considerable room for ambiguity and interpretation by the reader. This time the relationship is between a psychologist and his young female patient in a science-fiction setting in which both appear to have visions foreshadowing an alien contact. As the story proceeds, their relationship develops, but once more goes nowhere.

His latest book, Celestia, is as refined as his previous works: it is set in a Venice of the future, which seems almost to come out of a dream, as elusive and labyrinthine as the real one.

30

Lrnz, Golem, 2015

Lrnz

Illustrator, graphic, animator, musician, Lorenzo Ceccotti, aka Lrnz, is an all-round artist figure. Balancing among comics, design, and contemporary art, Lrnz is an assiduous experimenter of expressive forms, materials, technologies. For him, in fact, comics are just one of countless means possible. His main comic work is Golem (2015), an ambitious graphic novel set in a sci-fi Rome in which the consumerism of big corporations has emptied and somewhat replaced the Italian State. If the plot is the classic story of rebellion to an oppressive system carried on by young outsiders, Golem’s visual expression is complex and layered, combining the more disparate influences, coming from Japanese comics as from Western ones, from fine arts as from industrial design. The result is fresh and dynamic, explicit in its references but never derivative. The editing, the framing choices, the drawing style that can take on the most varied registers, and the refined use of color make it one of the most interesting books in the recent Italian panorama.